In episode 30 of the Fine Art Photography podcast, we explore ideas of photography as a way of immortalizing the subject and the photographer

Full written transcript

In this episode — Vita brevis, ars longa: photography as a form immortality

Vita brevis, ars longa. So said Hippocrates. That translates to “Life is short, and art is long . . . “

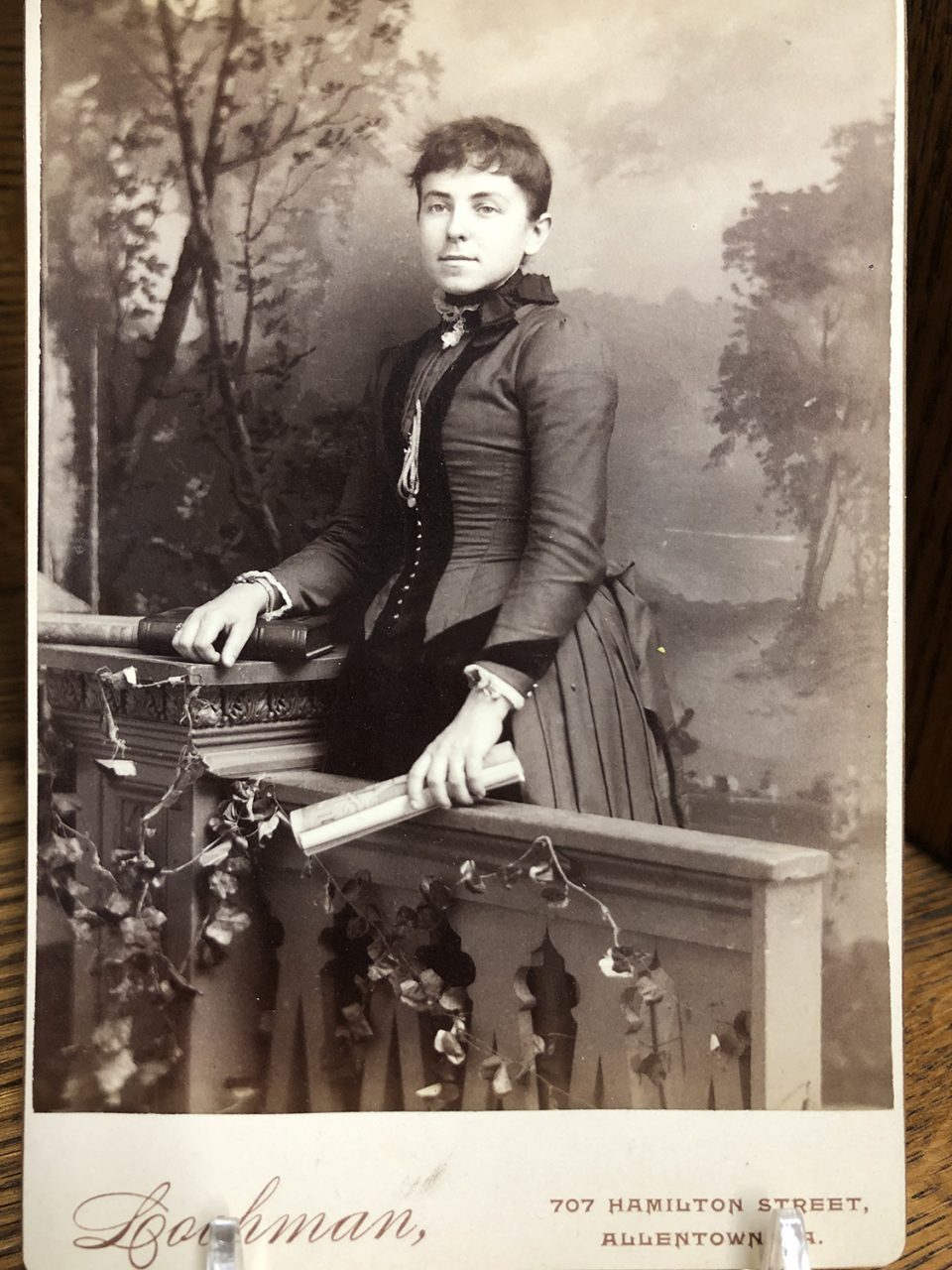

In my first ever podcast episode, I talked about how I bought a small antique albumen print — a studio portrait of a young woman made in Pennsylvania in the 1880s — and in that episode, I learned totally randomly through research that I was a very distant relative of the photographer’s wife. But the point I want to make for this episode is that the subject of the portrait — that pretty young woman with dark hair and a baby bump under her primm Victorian dress — can still stare out at me across the generations. I don’t know the model’s name or anything about her life. I don’t know what — if anything — of her long-ago life has carried forward into modern times — perhaps this photograph is the ONLY remaining proof of her existence 140 years later. It’s possible her own descendants don’t even remember her or know about her life.

That’s the true miracle of photography. It preserves the instant forever. In a way, that photograph immortalized the model, but also the photographer. His name is on the portrait card and I was able to learn a lot about him, including the fact he was probably married to a distant cousin of mine.

Photographs allow us to reach back into time and look at the face of someone like Abraham Lincoln. But while great people like Lincoln would have been immortalized and remembered in many ways, photographs also allow us to see the faces of ordinary people like a foot soldier from the Revolutionary War, Baltus Stone, captured on a daguerreotype in 1846 at around the age of 101. He fought in several battles in the war of independence, he supposedly served under George Washington, and he was probably captured by the British. He spent the rest of his life as a day laborer earning an $8 a month government pension for his war service. But without a single small portrait that has miraculously survived since 1846, Baltus Stone would be completely unremembered.

By the way, that small daguerreotype portrait of Baltus Stone is now valued at $50,000 — a sum probably unimaginable to Mr. Stone in his lifetime.

I won’t lie — one of the reasons I make photographs is because I want to leave something behind after I’m gone. I hope at least some of my art will endure. It’s a form of immortality — a legacy.

In her book On Photography, writer Susan Sontag said all photographs are memento mori. The term “memento mori” is Latin and it translates into something like “remember you will die,” or “remember you are mortal.” Oh, those light-hearted Romans!

Susan Sontag was saying that the very act of making a photograph of someone reminds us that the person won’t live forever. In fact, by the time you click the shutter, the very instant of the photograph itself is already gone.

I choose to take a less dark attitude about photography — more akin to another Latin phrase — carpe diem — usually translated as Seize the Day. I like to seize the opportunity to capture beauty anytime and anyplace I find it, with the goal of preserving it and presenting it to a broader audience. After all, while most things we photograph won’t last forever and neither will we, the photographs we make can represent us well into the future.

What got me thinking about this was a story I read this week in ARTNET news about a new form of rock art just discovered in Australia that’s between 6,000 and 9,400 years old. They say this is a never-before-seen style of rock art that now bridges a gap between a much older style that’s 12,000 years old, and more recent work that’s 4,000 years old.

How can we mentally comprehend these types of time scales? In the Lascaux caves there’s art that’s 15 – 17,000 years old. In the more recently discovered Chauvet cave in France, there’s art that’s been dated up to 33,000 years old. Some of that art shows evidence it was drawn-over or added-to by subsequent artists over a period of maybe 8,000 years. People went back there time and again, generation after generation to make a collaborative form of art over a period of 8,000 years!

One thing is clear — humans have always had an urge to make an artistic mark. Whether these ancient artists intended or wished for their marks to last forever is unclear. The art was most likely part of some kind of ceremonies or rituals that we have no way of understanding. Native Americans have said that their petroglyphic art was never intended to last. To them, the natural erosion and loss is part of its magic and part of its story.

Most likely, those cave artists didn’t consider themselves artists at all. They may have been tribal leaders, or priests, or shamans, or pious pilgrims. Consider the example of the gorgeous and elaborate Navajo sand paintings, which are meticulously created as part of a healing ceremony. They are not considered by the Navajo as art, but as medicine. They are destroyed at the end of the ceremony to destroy the illness.

As I said before, as an artist with an ego — I want my work to last. My hope is that someone will still look at and admire something I’ve created long after I’m gone. Of course that means I hope it will be relevant to people, but also that it will actually still exist. To accomplish that, it’s partly about digital presence obviously — although we have no way of knowing how digital work will last over the coming decades. While that photo print of the young woman I mentioned earlier is very well preserved and looks practically new after 140 years, there may be no Instagram 140 years from now. There may not even be an internet, or it may be very different than what we experience today. Changing technologies could make our digital things inaccessible or lost to future generations.

Here’s an example. The Cincinnati Public Library owns a series of 8 daguerreotype prints that –when placed side by side — make a continuous panorama of the Cincinnati waterfront as it looked in 1848. Researchers claim the clarity and resolution of each daguerreotype plate is equal to a 140,000 megapixel digital image — yes I said 140,000 mega pixels in each plate. The folks in Cincinnati asked experts at the George Eastman House — the famous photography museum in Rochester NY — to make digital copies with minor cleaning and restorations. Those were posted online in 2010 as Flash files that could be enlarged and explored with great clarity.

Supposedly, you can see most minute details in the images. You can see individual persons on the streets. You can see buildings, signs, and riverboats that no longer exist. You can read the time of day on a clock tower, but the face of the clock in the photograph is less than a millimeter across. This is one of the earliest and best photographs of an urban area in existence.

So what’s the problem? The problem is that Flash technology no longer works on most computers now. The ability to delve deeply into the images is lost, even though the images can still be found online in other formats. Flash was common in 2010, but in 2020, it’s extinct. That’s only ten years. If you go to the original website now, you’ll see a broken plug-in graphic that says Flash is not permitted or something to that effect. My point is that digital methods may or may not carry forward as a reliable way of preserving or presenting your photographs.

By the way, if you want to see those Cincinnati waterfront images, I’ll include a link in the description.

There’s been a lot of articles written about the vast numbers of photographs that are uploaded to sites like Instagram everyday. But how many of them will still be around in future decades?

I used to think the answer was to burn backups of the files to CDs or DVDs. But the truth is, as stable as they appear, those disks won’t last forever — they degrade over time. But the even more pressing question is how could you actually access your own CDs even now? Almost no computers come with a CD drive anymore.

If you archive your images to a hard drive, the files may endure on the media, but what if no one can find the correct cable to access the drive in 20 years?

Cloud storage? That’s a good option for now, as long as you keep the subscription active.

For me it always comes down to prints. I make quality prints because I want the person buying the art to be able to display it for a lifetime. But in theory, all the prints I sell now should last much longer than a human lifetime — potentially up to 400 years without serious degradation — maybe even longer. I quote that number based on studies and testing by Wilhelm Imaging Research. I have romantic notions that perhaps a few framed Keith Dotson photographs might still be lingering around on someone’s wall in 400 years. Hey it’s my podcast — let me fantasize.

That 400-year number applies to certain inkjet slash paper combinations. Correctly processed and washed silver gelatin prints are also considered extremely archival, but platinum prints are the most permanent form of photographic print. The image itself, made with platinum metal, is theoretically eternal. The only weakness is the type of paper or substrate that’s used to make the print — and a good quality paper made of cotton or other stable materials could last a very very long time with proper care and maintenance — a thousand years maybe? Longer?

What are your thoughts on the idea of photographs lasting through the ages? Do you view your own photographs as a legacy? Do you care if your images last beyond a few decades or if they are still being seen after you’re gone? Do you make prints of your photographs or are you satisfied with digital places like flickr or smugmug or 500 pixels or Instagram?

And if you make prints, where do you place them? In frames on a wall? In family photo albums? In printed books from someplace like Blurb? Or just loose in a shoebox?

Before I wrap this up, here are the words of a handful of great artists on the topic of art and immortality:

William Faulkner said, “Since man is mortal, the only immortality possible for him is to leave something behind him that is immortal . . . This is the artist’s way of scribbling ‘Kilroy was here’ on the wall of the final and irrevocable oblivion through which he must someday pass.”

Artist Leonard Baskin said, “Art is man’s distinctly human way of fighting death.”

Romare Bearden said, “Every artist wants his work to be permanent. But what is? The Aswan Dam covered some of the greatest art in the world. Venice is sinking. Great books and pictures were lost in the Florence floods. In the meantime we still enjoy butterflies.”

Anthony Burgess, who wrote A Clockwork Orange, said, “In two thousand years all our generals and politicians may be forgotten, but Einstein and Madame Curie and Bernard Shaw and Stravinsky will keep the memory of our age alive.”

Just food for thought everybody. Thanks for listening — I’ll talk to you again real soon.

Sources and Links

“Archaeologists Have Discovered an Extraordinary New Style of Aboriginal Rock Art That Honors the Human-Animal Bond” Artnet, Sarah Cascone, October 6, 2020

“1848 Daguerreotypes Bring Middle America’s Past to Life” Wired, Julie Rehmeyer, July 9, 2010

“He Fought with George Washington: Amazing Daguerreotype of a Revolutionary Soldier born in the 1740s” The 19th Century Rare Book and Photograph Shop

Cover photograph: One of 8 daguerreotype photographs of the Cincinnati waterfront made by Charles Fontayne and William Porter in 1848. Image courtesy of courtesy of the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County.

Note: This blog post contains an Amazon Affiliate link. I may earn a commission on qualifying purchases.

I haven’t listened to the podcast, I just read the transcript, but I still resonate with everything you said here: I think about the durability of what I create a lot. I’m also very interested in life extension and I wrote a short book on the topic of legacies called: What is your legacy? 101 ideas on getting started to create and build one.

Now getting back to the durability of what we create, there are 3 main aspects here:

1. The longevity of the artist’s lifespan and especially one’s creative longevity and size of output – the more you create, the more likely something of you will outlast you.

2. The durability of the “canvas” you choose for your art: I’ve noticed in history museums that artworks most likely to survive were either sculptures made in stone or ceramic vessels buried underground during funerals.

3. The redundancy of one’s art: original artwork available in one copy only (even if stored in museums in controlled environments) is less likely to survive compared to art replicated many times, especially on merchandise or art decorating useful things. The latter has the advantage of being useful too, not just beautiful. Another thing I noticed is that art is more likely to survive if it is a source of revenue as heirs or even society at large (e.g., when copyright expires) are more likely to put time and energy in such art.