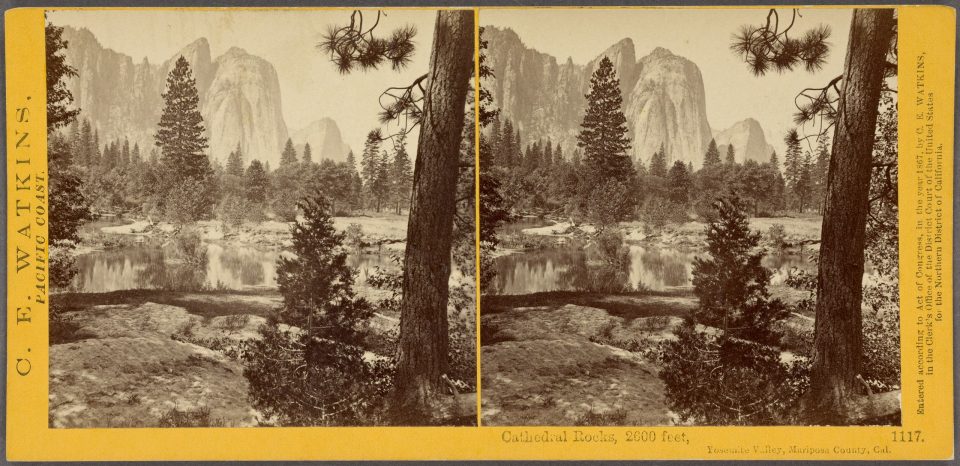

Carleton Watkins set the standard by which all other Yosemite photographers were measured

If I say the words “great Yosemite landscape photographer,” you’ll probably think of the legendary Ansel Adams. But Ansel wasn’t the first great photographer of Yosemite landscapes.

That honor goes to Carleton Watkins, a native of Oneonta, NY, who travelled to California to find his fortune in the big 1849 Gold Rush. He initially found work running deliveries from Sacramento out to the gold mines with a friend from Oneonta, Collis Huntington, who later became a wealthy railroad magnate.

Watkins went on to work a variety of other odd jobs — he was a clerk in a book store for a while before becoming an assistant to several local photographers.

Smithsonian Magazine relates an amazing story about how Watkins got his first photography job:

Watkins failed to hit it big in gold and a few years later, he was in San Francisco working as a store clerk when the owner of a photo studio noticed his congenial ability to please customers. When the studio’s photographer quit suddenly, the owner asked Watkins to pretend to be a photographer–to try to keep portrait customers happy until a real photographer could be hired. But Watkins learned camera techniques quickly, was fascinated by the medium and was soon working as an actual photographer in San Jose and San Francisco.

It’s hard to know if he was drawn to photography because of love and artistic passion, or if he simply undertook it as a way to earn a living, but by the late 1850s, his work was in demand. His landscapes were used by a magazine as reference material for engraved illustrations. He made photographs to be used as evidence in the courts. And he was hired to document the estates of California bigwigs like the Fremonts (source). He also became the official photographer of the California State Geological Survey.

As American expansion surpassed the mountains and reached the west coast, “armchair travelers” (Alinder) in the eastern US and Europe were all aflutter about the magnificent landscapes (and the native peoples) of the American West, and there was a market for landscape photographs of the region.

In 1861, just as the American Civil War was breaking out, Watkins made his first trip to Yosemite. He carried a large camera, at least 30 large glass plates, a stereoscopic camera, and all the necessary chemistry and accoutrements into the field to make large format landscape photographs.

Keep in mind, these were still early days in the existence of photography. Carleton made what are called wet plate collodions, which means that he traveled with a portable darkroom in a wagon (although some sources say he used a tent for a darkroom). Each glass plate had to be cleaned, coated with the wet emulsion in total darkness, inserted while wet into the negative carrier, carried while still wet into the daylight to place into the camera. Then after exposure, removed back to the darkroom for development.

I seriously don’t know how these early photographers did it. But that’s not all.

After spending weeks, or even months, in the wilderness, the photographer then had to make the precarious journey back across bumpy roads, along mountainsides, and over rough terrain, hoping that their precious work didn’t become shattered during the journey. I read that photographer Edward Curtis once lost a wagon over the side of a hill, destroying his glass plate negatives in the tumble.

So, no, this was not an occupation for the faint of heart. But it paid off for Watkins. His Yosemite pictures were a hit, so successful in fact that he won many important international awards. He became friends with socialites and luminaries. He held large gallery exhibitions, and his glorious landscapes influenced congress to pass legislation to protect the Yosemite Valley, signed by Abraham Lincoln in 1864. This set the precedent for what would eventually become the National Parks System.

(Side note: Isn’t it remarkable that in the midst of the brutal American Civil War, our government managed to do other things like protect public lands? It shows a lot of optimism for the future of the nation.)

Eventually Watkins opened his own gallery, the Yosemite Art Gallery in San Francisco, where he sold his prints in black walnut frames with gilt-edged mats. His work was so extravagant that he received complaints about the prices.

Unfortunately, Watkins story isn’t one with a happy ending.

Although he was a brilliant artist, Watkins wasn’t a successful businessman. His work was pirated and his copyrights infringed. He lost most of his photographs to a creditor during a difficult financial recession in the 1870s, forcing him to start over rebuilding his collection of images. He eventually had to find work as an employee in the same gallery he once owned.

Watkins became plagued with health problems and poor vision, and then he received the worst blow of all — his studio and all of his remaining glass negatives were destroyed in the big San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906.

A few poignant paragraphs from Mary Street Alinder’s terrific 1996 biography of Ansel Adams describe the highs and lows of Watkins life. She closed her discussion of Watkins on page 32, with this sad statement . . .

Sadly, Watkins himself was stalked by poverty, losing his gallery and most of his negatives to bankruptcy in 1874. Still determined, he returned to the same sights and rephotographed them in an attempt to build a new archive of material. But his downfall continued with his blindness in 1903 and the destruction of his glass plates and most of his prints in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. His family eventually committed him, a broken man, to a mental hospital, where he died in 1916 and was buried in an unmarked grave.

Watkins never struck it rich in the gold rush, but his golden sepia prints are certainly a treasure for us all.

Carleton Watkins final resting place

There’s a cenotaph stone in place for Watkins in the Riverside Cemetery in Oneonta, NY.

But, as noted in the Alinder passage above, Watkins actual burial place is an unmarked grave plot at the Napa State Hospital Cemetery in Napa, California.

Thanks for reading!

Be sure to visit me on Facebook, Google+ or Pinterest, or on my website at keithdotson.com.

~ Keith

Books about Carleton Watkins

This page features a nice selection of books about the life and work of Carleton Watkins on Amazon, including The Stanford Albums.

Sources:

- Ansel Adams: A Biography, Mary Street Alinder, page 31-32, Henry Holt and Company, New York, 1996

- carletonwatkins.com

- J. Paul Getty Museum, “Carleton Watkins”

- Smithsonian Magazine, “About Carleton Watkins“

Notice: This post contains Amazon Affiliate links.