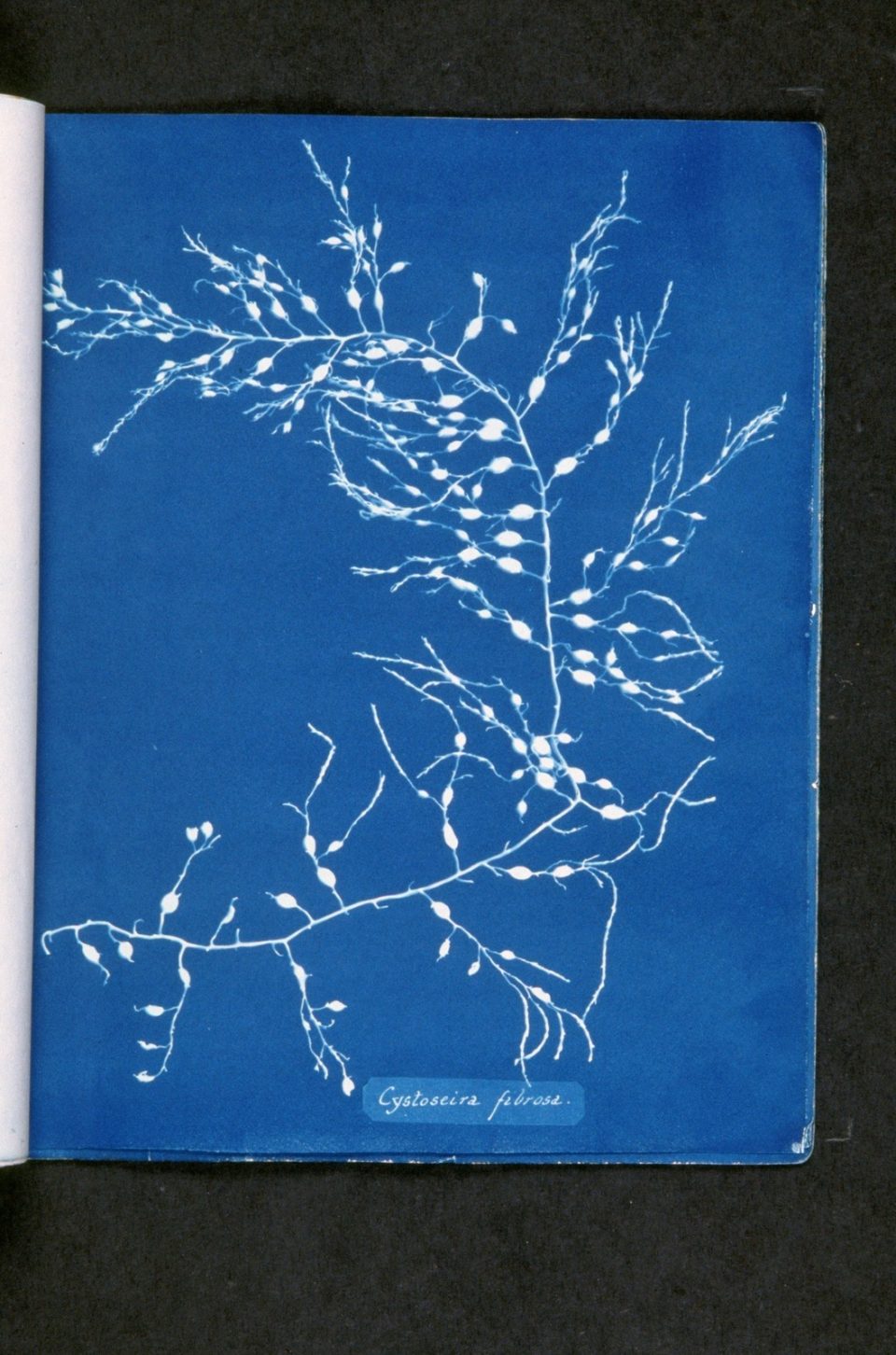

In this episode, a brief biography of Anna Atkins, the first female photographer and the first person to create a photography-based book. She learned photography from some of its inventors and went on to become a master of the cyanotype print.

If you’d rather read about Anna Atkins than listen to my voice, scroll down to see the full transcript of the episode at bottom.

Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-4b47-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Sources mentioned in the podcast

New York Public Library full digital copy of British Algae by Anna Atkins

“The 19th-Century Botanist Who Changed the Course of Photography,” by Alina Cohen on Artsy

Sun Gardens: Victorian Photograms

Hardcover book mentioned in the podcast, available on Amazon

Other sources:

“Blooming marvellous: the world’s first female photographer – and her botanical beauties,” by Joanna Moorhead on The Guardian

See some of my own cyanotype prints here

Thanks for reading.

Be sure to visit me on Facebook, Instagram or Pinterest, or on my website at keithdotson.com.

~ Keith

NOTE: This article contains Amazon Affiliate links. I may receive a small payment for qualifying purchases.

Full transcript of the podcast, ‘Anna Atkins: England’s Blue Lady of Photography’

The beginnings of photography occurred in the early 1800s — a time when it was very much a man’s world, which of course means most of the early pioneers and innovators were men. But not all. In this episode, I’ll talk about a true photography pioneer — Anna Atkins, who is probably the first woman photographer in history, and is known to be the first person in history to create a book of photographs.

Here’s a passage from the New York Public Library about Anna Atkins: “Anna Atkins was the first woman photographer. She was also the first person to print and publish her own book illustrated entirely by photography. This work, British Algae, made clear the enormous potential of William Henry Fox Talbot’s 1839 invention of photography on paper as, in his words, ‘every man his own printer and publisher.’ Moreover, Atkins’s work showed how the new medium could overcome, as she wrote, ‘the difficulty of making accurate drawings of objects as minute as many of the Algae and Conferva,’ by the use of ‘Sir John Herschel’s beautiful process of Cyanotype, to obtain impressions of the plants themselves.’ “

From that quote we can discover a few things about Anna Atkins. First, she was friendly with all of the male pioneers of photography in England. She knew William Henry Fox Talbot. She knew Sir John Herschel, the inventor of the cyanotype process that she mastered, and probably learned the process from Herschel himself. Also, she was a botanist — so her photograms of algae and other plants were more about her interest in the science of botany than an interest in art. Her books of cyanotypes were reference books, not art books.

Anna Atkins was born Anna Children in Tunbridge Kent in 1799, the only child of scientist John George Children and Hester Anne Children. Hester Children had difficulties with the childbirth and eventually died in 1800. Anna herself died childless in 1871 at age 72.

Anna’s father was a chemist, mineralogist, and zoologist, and he raised Anna with an education in science that was unusual for women in that era.

First, let’s talk about the notion of Anna Atkins as the first female photographer — maybe, maybe not.

Anna learned about William Henry Fox Talbot’s photography innovations directly from the man himself. She had access to a camera as early as 1841 — however, Talbot’s wife also made photographs. Although Anna Atkins is commonly considered to be the first female photographer, none of her camera-based photographs have survived, and neither have any from Constance, wife of Mr. Talbot, so we may never know who was truly the first female photographer. Regardless, Anna Atkins was definitely a pioneer.

While her camera-based work didn’t survive, her cyanotype photograms of algae, ferns, flowers, grasses, and other plants are still wonderful examples of the beauty that can be achieved through the cyanotype process. She actually recorded every type of algae present in the British isles.

In case you aren’t familiar with it, the cyanotype process is one of the earliest and simplest forms of photographic printing. It’s a form of contact printing done in the sunlight, which means you sandwich a large camera negative or an actual object like a flower or whatever, onto the printing paper. The paper is made light sensitive with two chemicals, ferric ammonium citrate and potassium ferricyanide, and after exposure in the sun or other UV light source, the print is developed in plain water, turning it a vivid color blue. Cyanotypes are better known today as blueprints like those seen in the hands of architects and construction managers.

The New York Public Library provides a full scanned version of her book online. Check the description for a link to that.

After Anna Atkins’ death, she wasn’t widely renowned and she faded in and out of history for a while. In a fantastic article about her life on Artsy dot net., Alina Cohen describes the journey her reputation took from anonymity to acclaim over the next 150 years.

Prior to Anna’s death, William Henry Fox Talbot wrote about non-silver photographic processes, praising Anna Atkin’s work but not identifying her by name. Based on Talbot’s writing, Scottish book collector William Lang Jr. began seeking a copy of her book, but didn’t locate it in London until 1888, well after Atkins’ death. Since she signed her work AA, Lang mistakenly assumed the initials meant anonymous amateur. He published an article about Atkins’ book in 1889–90 which was read by a curator from the Natural History Museum in London, who also owned a copy of Atkins;’ book and knew her to be its author.

After learning the true name of the book’s author, Lang initiated a series of lectures and exhibitions about Atkins and her work. But her reputation wasn’t safe just yet. Later in life, Lang needed money and was forced to sell his copy of Anna Atkins’ book. As Artsy says it, she lost a major champion.

A history of photography published in 1955 mentioned her name with a few sentences about her.

In the 1970s, a University of Texas art historian named Larry Schaaf rediscovered Atkin’s work, and began a biography of her. Artsy credits Schaaf with identifying her as both a pioneer of photography and the first person to publish a photography-illustrated book. He went on to publish book about her work in 1985 called Sun Gardens: Victorian Photograms.

Her work has since been widely exhibited and is included among some of the world’s premiere museum collections.

Atkins and other early photographers’ instinct to use photography and photograms as a descriptive medium — in other words, she favored them as a form of scientific illustration over traditional drawing and painting, may have helped create a problem for later photographers who wanted the medium to be seen as more than simply a true recording of nature.

The Pictorialism movement was a soft-focus artsy reaction to the medium’s critics, who said it’s not an expressive art like painting, but just a technology for making accurate representations of the world.

Having said that, I don’t mean to downplay the artistic beauty of Anna Atkin’s photograms, because they are gorgeous images in and of themselves.

Fascinating! Thank you for finding these rare historical nuggets! And for supporting women photographers everywhere,