A humorous anecdote from the January 3, 1891 edition of Wilson’s Photographic Magazine

Apparently, back in the early days of photography, magazines included lifestyle pieces and humor. Such is the case with this strange little story of a young man who broke up with his lover over the brand of camera she chose to sling over her shoulder.

Below, you’ll see a live text version followed by the original typeset pages.

SKETCHY EXPERIENCES.

By a New Contributor.

I find a little piece of intelligence in the December number of the Boston Law and Gospel which is calculated to give consolation to all who have a kindly leaning toward the fitness of things. It runs thus:

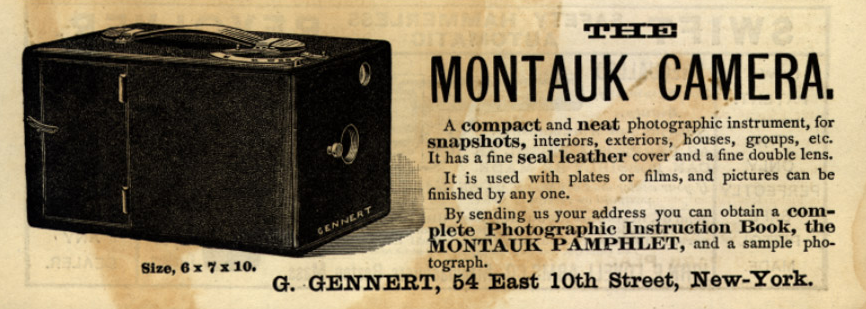

Last summer, at Nahant, a young lady appeared at one of the fashionable hotels with a “Montauk” hand-camera swung over her shoulder. In a few days after (all accident, of course) her betrothed lover appeared with a “Kodak” under his arm, nearest to his heart. They quarrelled, and he broke the engagement. He could not marry anyone who would use a Montauk, made in a city of uncertain population and the headquarters for N.P.A. paper. Now the jury awards her $1000 in a breach of promise suit.

The fair damsel, of course, did perfectly right in holding on to her Montauk. She would have splashed her courage of conviction (one of the greatest charms of her sex) all into a saturated solution had she done otherwise. What a painful lack of true grit she would have shown also. Of course, it is not always easily seen why one person holds so tenaciously to one kind of a camera, while his next best friend as persistently clings to another. But if the young lady preferred the Montauk, she was heartily to be commended for sacrificing everything for it. I have known one’s favorite camera cause him to do the most strange things imaginable. I have been there my own-self. But is not that correct — is it not right? In the case in question, the lover was unquestionably in the wrong. In breaking his engagement with her because she was manly enough to lift up her voice in favor of the Montauk when it was her choice, he proved that he was considerable of a donkey. A swain who conducts a courtship — as he evidently did — to the motto :

“I could not love thee, dear, so much,

Loved I the Kodak not much more,

writes himself down in large distinct light and shade as an animal of the sort I have named, and leaves all our camera clubs in doubt as to his integrity. Why, such a man would steal a roll-holder out of a dead soldier’s pocket on the field of battle.

Any attempt to introduce the camera into love and courtship ought to be sternly frowned down upon by us all. Our politics, our religion, and our photography we are all individually and alone accountable for, and should be allowed to choose unbiased for ourselves. Some people think photography is too much discussed in society now, anyway. Particularly are the people of Asheville still of this mind. Once every year the nation is thoroughly torn up from ocean to ocean by the Convention and exhibition of the P. A. of A., and in the months between, some of us hear of nothing else. Perhaps we should not object to this in our photographic societies. But let the photographic line be drawn somewhere. Let it be drawn at courtship, if you will. It is desirable (and at the new year beginning is a good time to begin) that the young American should be taught that he must enter the drawing-room of the hotel parlor, where the idol of his soul is awaiting him, whispering to himself,” He who enters here leaves photography behind “If the donkey of whom (or of which?) the Law and Gospel tells had not been injured to the focus of $1000, others of his kind in whom photography is so strong — and camera prejudice so mighty — might feel encouraged to imitate his wretched example. As a consequence, the dry-plate maker and the apparatus producer will suffer.

There was a time when young lovers used to spend their time in singing duets, playing croquet, reading Lalla Rookh, getting up amateur theatricals, discussing Browning, swinging on the front gate, and in similar light-hearted employments, because the detective camera did not assail them on all sides. Happily, by agreement this annoyance has ceased in some quarters. Shall lovers now begin to take such a profound mutual interest in cameras that if one of them cheers for one, the other will proceed to break the engagement if that one is not the one he is focussing? It may be said that the girl in question began the row by cheering for her Montauk. But that’s nonsense. The man — that is to say, the donkey — was at fault for taking the cheers seriously. What he ought to have done, and would have done if he had been another sort of a created being, was to cheer her for cheering, without, of course, modifying his own camera convictions. If he had pursued that tolerant, generous-hearted policy, it is more than likely that the girl would have been so infatuated with his chivalrous nobility of character that she would have renounced the Montauk on the spot and have embraced the Kodak.

As it is, the two are separated. The young donkey has given up photography “on account of the McKinley bill,” and the travelling salesmen of several stock-dealers are after the young lady, pestering her to invest her $1000 heart-money in printing-frames inlaid with mother-o’-pearl, and in a burnisher made of aluminum!

Actual printed pages from Wilson’s Photographic Magazine, January 3, 1891

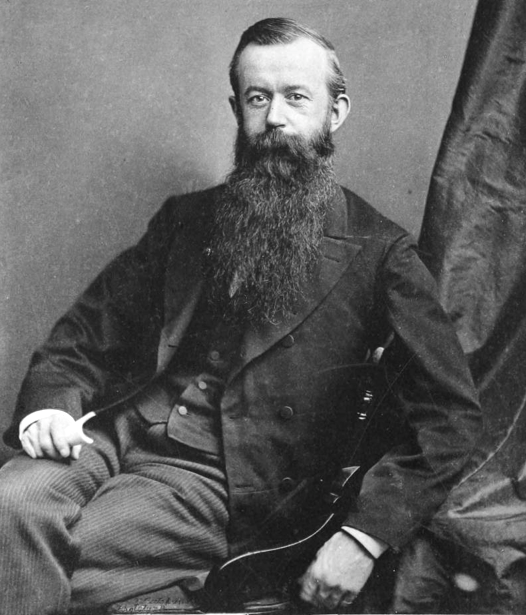

About Edward L. Wilson

Edward L. Wilson (1838-1903) was an American photographer, author, and publisher. In 1864 he began the Philadelphia Photographer magazine and in 1889 he began publishing Wilson’s Photographic Magazine in New York City. Wilson’s Photographic Magazine ran through 1914, and in 1915 was renamed The Photographic Journal of America running until 1923. The legendary photographer Edward S. Curtis was a reader and credited Wilson’s book Wilson’s Photographics: A Series of Lessons, Accompanied by Notes, on All the Processes Which Are Needful in the Art of Photography with teaching him photography.

You can buy a reprinted edition of that book on Amazon here.

Wilson also served as a member and officer of the National Photographic Association of the United States.

Thanks for reading.

Be sure to visit me on Facebook, Instagram or Pinterest, or on my website at keithdotson.com.

~ Keith

NOTE: This blog post contains an Amazon Affiliate link. I may earn a small commission on qualifying purchases.