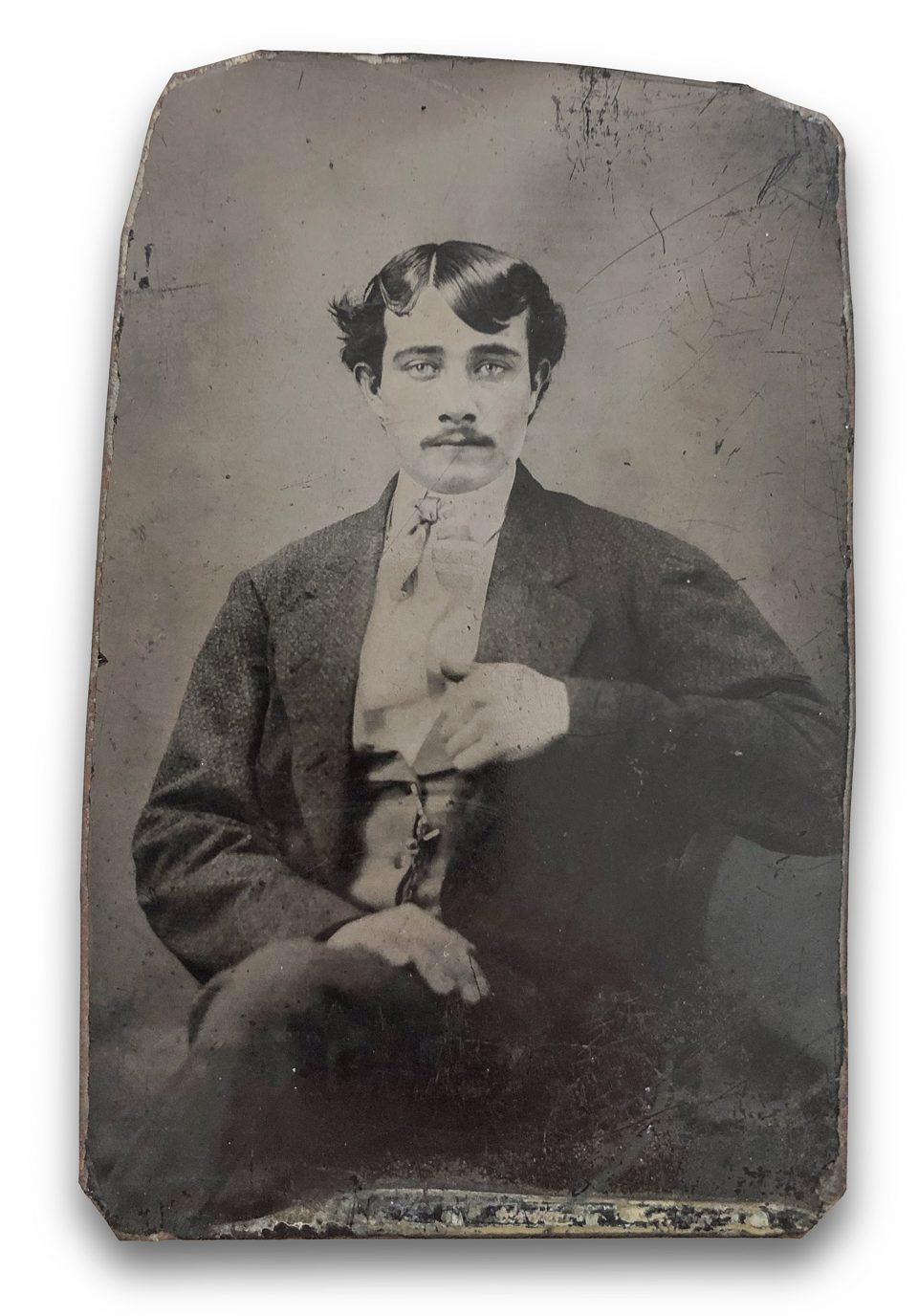

Sixth-plate “bon-ton” tintype shows a handsome young man with blue eyes and his hair slicked down for his portrait

The actual size of this crudely sheared piece of iron is approximately 2.5-inches wide by 3.75-inches tall.

While this photograph is undated, it was probably made in the 1850s-60s. And since tintypes show no hallmarks of the photographer like later cabinet cards, the location, photographer, and sitter are all exceedingly difficult to identify.

About tintypes

The tintype, as it was popularly called in its era, was also known as the ferrotype and the melainotype.

The process was first defined in France in 1853 by Adolphe-Alexandre Martin. It was patented in the U.S. and in the U.K. in 1856. Even though this is a historical process, tintypes are still made today as a niche process.

A tintype is a direct original print made on a very thin sheet of iron — not actually tin — hence the other name ferrotype. A “direct original” is a print is made directly onto the final piece of metal, with no intermediate negative. Ambrotypes were popular prior to tintypes — and that was a process with the photograph made onto a sheet of glass, then backed with black to reveal the silvery image on the glass. If held in the original case behind a sheet of glass, a tintype can sometimes be hard to distinguish from an ambrotype.

While beautiful, ambrotypes — being imprinted onto glass — were quite fragile, whereas tintypes have proven to be durable.

Many more tintypes exist today than ambrotypes, and tintypes can be found in antique shops for a bargain. They’re all portraits, and that’s what you’ll find — photography in those days was primarily a portrait business.

The rise of affordable and comparatively easy-to-make tintypes timed perfectly with the American Civil War. Families wanted portraits of their boys going off to war. Soldiers wanted pictures of their mothers, wives, or girlfriends to carry in their pocket as they marched off to battle.

Because they were durable, many of our important surviving photographs from the later half of the 1800s are tintypes.

In fact — the most famous photograph of Billy the Kid — which was until recently also the only known photograph of him — is a tintype. Since tintypes were portraits and were unique originals, likely they were held in the hand of the subject. That’s almost certainly true of all tintypes — at some point, the person in the photograph also held that very same photo in their hands. That’s a pretty cool direct connection to the past.

A tintype is typically a unique original with no intermediate negatives, meaning that it would be the only print. . . a one of a kind.

But that’s not always true. Thanks to an ingenious development in 1858, the Gem Ferrotype was born.

Starting in 1858, Gem Ferrotypes allowed creation of multiple small duplicates on a single sheet of larger metal thanks to the invention of a multiple lens camera. The sitter was projected multiple times in one single exposure. This would then be cut down to provide a set of small duplicates very affordably. Gem Ferrotypes were about the size of a postage stamp. They were popular for lockets and broaches, but also were often sold in small paper inserts that acted as a decorative mat. These are useful today for identifying the photographer because they sometimes had the photographer’s information printed on the back. Although one article claimed that fewer than 20% of photographers actually published their names on the cards.

Some tintypes were also sold in decorative frames, like those used for ambrotypes and daguerreotypes. One article said that loose Gem Ferrotypes were sold for ten cents a dozen. Gems sold in paper mats were fifty cents a dozen. Framed photographs would have been more.

Tintypes sold for prices averaging from 25 cents to $2.50 in the United States. Some photographers charged as much as $20.00 for a sixth-plate portrait.

Cased images typically include the image plate and a cover glass wrapped together in a brass mat, placed inside a leather or thermoplastic case.

Tintypes were quite often hand tinted, with the photographer carefully applying a blush of red to the sitter’s cheeks. This was done to both men and women — and the most bizarre use of this I ever saw was on a death photo made of Civil War guerilla fighter Bloody Bill Anderson. After his death in a bloody gunfight with Union troops in Missouri, he was propped up on a board and photographed, clutching his pistol, eyes closed with a grisly grimacing smile on his face. For some inexplicable reason, the photographer added a rosy tint to the cheeks of a corpse, and also colored some flower patterns on his shirt.

Tintypes were sold in sizes related to the size of the metal plate. According to the Library of Congress, the common plate sizes were as follows …

- Imperial or Mammoth Plate – Larger than 6.5 x 8.5 inches

- Whole Plate – 6.5 x 8.5 inches

- Half Plate – 4.25 x 5.5 inches

- Quarter Plate – 3.25 x 4.25 inches

- Sixth Plate – 2.75 x 3.25 inches

- Ninth Plate – 2 x 2.5 inches

- Sixteenth Plate – 1.5 x 1.75 inches