I’ll describe the experience of seeing the world’s oldest known photographic image, with some history of how it was made

Or, you can also listen to my podcast episode to this topic:

If you’re reading this, you’re obviously interested in photography. You may be a pro photographer, an enthusiast, a student or a teacher, or you might be someone interested in collecting photographs.

I’m curious though — do you ever go see photography exhibits in person (or did you before the world got so weird)? If not, I encourage you to make an effort to visit a museum exhibition or a photo exhibit at a gallery in your city as soon as you can safely do that.

There’s something so exciting about seeing beautiful photographic prints in person — especially if it’s one of the world’s great photographs. It’s almost like glimpsing a famous musician or movie star at the airport — you know you’re in the presence of greatness. The sensation is electric.

I love seeing the tonalities, the detail, the sharpness or blurriness — after all not all great photographs are in focus! I love seeing the surface of the paper — is it matte or glossy, smooth or textured? Is the print toned? How is it matted and framed? And — this is a big one — I love seeing the photographer’s signature on the print.

I’ve seen the works of many great photographers in person — I saw a large portrait of Groucho Marx by Richard Avedon — beautiful!

I saw an exhibition by Steve McCurry — many of his prints were grainier than I expected. Afghan Girl is as stunning as you would imagine.

I have seen a few prints from the collection of Vivian Maier — beautiful but printed quite small. You had to stand close to see them well.

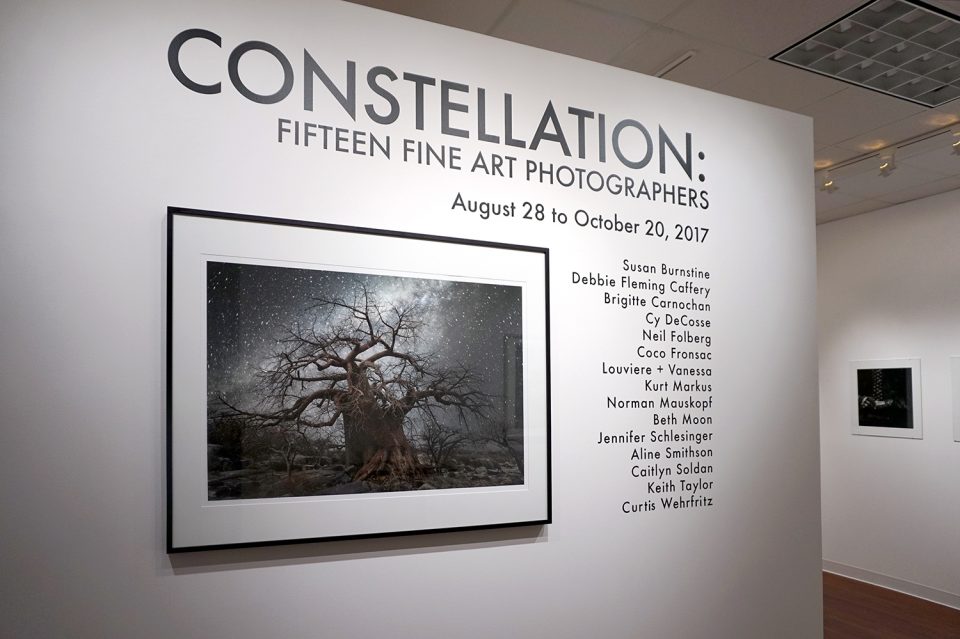

I’ve seen photographs by Annie Liebovitz, William Eggleston, Ansel Adams, Jerry Uelsmann, Beth Moon, and many others.

Seeing the world’s oldest photograph in person

But as far as I can remember, I’ve only ever seen one photograph that was a true original and absolute one-of-a-kind. When I lived in the Austin metro area, I went to the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas to see the one-and-only “world’s oldest photograph.”

Yes, the famous “view from the window at Le Gras,” by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, the world’s oldest known surviving camera photograph made in France in 1827, has been deep in the heart of Texas since 1963.

I’ve actually been to see the photograph more than once. Originally, it was housed just inside the entrance of the imposing Ransom Center building, inside a small brick kiosk, carefully designed to protect the antique image. This tiny kiosk only allowed one or two people to view the image at a time. Later, the HRC was renovated and the photo was moved into a sealed window display inside its own specially-designed darkened room, nestled inside a fancy gold frame, encased in a heavy-duty protective outer box. The new digs allow the photograph to be protected while being visible to larger groups of visitors.

What do you see when you gaze at the small photograph? Honestly, not very much detail is discernible to the naked eye, especially in the dim light of the room. The print is quite small, 6.4 inches by 8 inches or 16.2 by 20.2 centimeters. When you look at the photograph, you see what essentially looks like a tarnished piece of metal in a gold frame, with a few faded markings. The Ransom Center includes manipulated reproductions and diagrams to help you understand what you’re looking at. One article quotes a curator at the Ransom Center as saying that the image is not faded by time, but is in fact, underexposed.

But even though the image is dim, make no mistake, you’re seeing a slice of time captured by a man far away in distance, and far away in years. You’re standing in sight of one of the world’s monumental achievements. If you think about it, you may get chills down your spine.

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, was a gentleman scientist, one of that breed of wealthy gentry who had the income and time on their hands to act as inventors and scientists. With his brother Claude, Joseph received a patent in 1807 for what was basically the world’s first internal combustion engine.

While Claude continued to tinker with the engine, Joseph explored his interest in capturing images with light and the camera obscura, which had long been in use by artists as a way of projecting images onto surfaces for copying.

Let’s be clear, the “view from the window at Le Gras,” wasn’t the first ever photographic image — it’s the oldest camera-based image known to survive.

It’s in fact known as a “heliograph” or light drawing, imaged onto a sheet of pewter that had been treated with Bitumen of Judea, a form of natural asphalt. It’s said that Nicéphore Niépce’ interest in the camera obscura came from his curiosity about the new art printing process called lithography, for which he lacked the necessary art talent. But lithography was a process where a copper, stone or glass plate was coated in a thin layer of bitumen, then drawn into by scratching through the bitumen surface. An application of acid would etch the exposed scratch marks making lines in the copper — then the bitumen was removed with solvents.

Nicéphore Niépce knew that exposing the bitumen to sunlight would harden it and make it less susceptible to the solvents. He had earlier produced photographic duplications of flat pieces of art, which no longer exist. Areas of the bitumen receiving more light would have been hardened at a different rates and therefore removed to varying degrees by the solvents. This is the basis for which the world’s oldest existing photograph was made.

The “view from the window at Le Gras” was a long exposure photograph. You can see in the Nicéphore Niépce photograph that the sunlight shines on two sides of the house, so the exposure may have lasted up to 8 hours. Because it’s a direct positive exposure onto the final media, rather than a print made from an original negative, it’s a reversed or flipped view of the actual subject.

There’s a fantastic Petapixel article about the world’s oldest photograph that includes modern photos of the location where the photo was made, even a photo of the exact spot in the window where the camera obscura was placed in 1827. It also includes photographs of the room where the photograph is displayed at the Ransom Center.

But how did the “view from the window at Le Gras” come to live in Texas?

The photograph remained in private ownership and exchanged hands in England several times throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. In the early 1950s, British collectors and historians Helmut and Alison Gernsheim were seeking the photograph as part of their research for their 400-page book The History of Photography.

They found the photograph in 1952, nearly fifty years after its last public viewing. The Gernsheim’s, apparently masters of promotion, began pitching “view from the window at Le Gras” as the world’s first photograph and taking it on widespread touring exhibitions.

The Harry Ransom Center acquired the photograph in 1963 along with the rest of the Gernsheim’s collection. The center has since been working to clarify the “world’s first photograph” claim — their website says this quote:

“The Ransom Center has taken a similar approach in its update to the exhibition of the heliograph, describing it as ‘the earliest known surviving photograph produced in the camera obscura,’ or a variation on that phrase, rather than ‘the first photograph.’ “

Ironically, parts of the University of Texas website still refer to it as “the first photograph.”

Lab tests at the Getty Conservation Institute

In 2002, the photograph left Austin for the Getty Conservation Institute for in-depth scientific testing for the first time ever. The Getty made a new, unretouched photographic reproduction of the image.

The Getty conservationists examined the photo under a microscope. They performed nondestructive X-ray fluorescence spectrometry and found the photograph was made on a pewter plate containing tin alloyed with lead, copper, and iron. They found that the pewter plate is irregular in shape and thickness. Infrared analysis of the image layer revealed a complex composition of bitumen and oil of lavender. The Getty researchers also identified an urgent need to upgrade the encasement of the photograph to keep oxygen and contaminants away from the photograph. That recommendation resulted in the current environmentally controlled case back home in Austin.

So we know what happened to the photograph, but what happened to Nicéphore Niépce? Did he increase his wealth with his innovations in photography? Actually, just the opposite — Joseph’s brother Claude went off to London, where he squandered the family fortune and became ill trying to find opportunities for the engine they invented.

Nicéphore Niépce photographic accomplishments were recognized in London and he was invited to present to present to the Royal Society, but being very guarded with his scientific secrets, he left out important details from his paper causing it to be rejected by the Society. This decision lead to a chain of events that essentially ceded the credit and publicity for “invention of photography” to Daguerre and Fox Talbot.

Claude died in 1828, and Joseph died in poverty in 1833 at age 68. Such poverty that his grave in the local cemetery was funded by the municipality.

Today, signs and markers in his hometown of Saint-Loup-de-Varennes hail him as a hometown hero.

If you find yourself in Austin, make time to go to the Harry Ransom Center to see this milestone in photography history for yourself.

Visit the Harry Ransom Center

Hours, maps, and parking directions are here.

Admission is free.

Thanks for reading.

Be sure to visit me on Facebook, Instagram or Pinterest, or on my website at keithdotson.com.

~ Keith

Sources

Introducing ‘The Niépce Heliograph’, Jessica S. McDonald

“Nicéphore Niépce,” Wikipedia

“The First Photo,” Harald Johnson, PetaPixel

“The Niépce Heliograph,” Harry Ransom Center

Results of Scientific Study on the First Photograph Unveiled during “At First Light, Niépce and the Dawn of Photography,” Harry Ransom Center

“View from the Window at Le Gras,” Wikipedia

NOTE: This blog post contains an Amazon Affiliate link. I may earn a small commission on qualifying sales.