Cave-in-Rock, Illinois was once home to pirate gangs, highwaymen, counterfeiters, and the Harpe Brothers — America’s first serial killers

In the video below, we walk around and into the Cave-In-Rock. We also walk onto the bluffs above, where the notorious Harpe Brothers stripped their victims naked and pushed them over the edge of the bluffs.

Scroll down for more history of this fascinating place.

Watch: Visit to and inside Cave-In-Rock

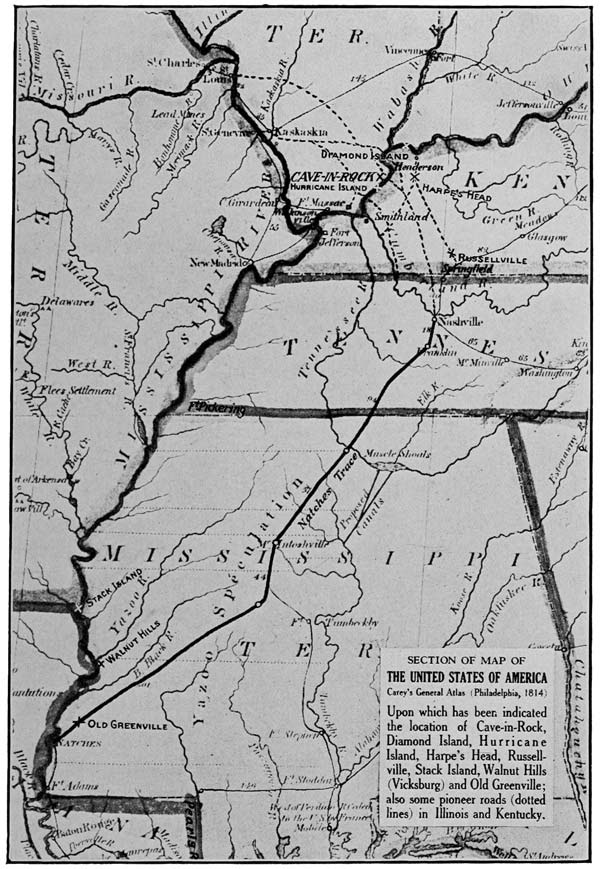

In the late 1700s and early 1800s, travel across the American countryside was a risky business. Some of the most popular routes, such as the Natchez Trace, an old Native American deep-cut footpath through the dense woods was haunted by highwaymen and bandits, many of whom were quite likely to kill their victims after taking their valuables.

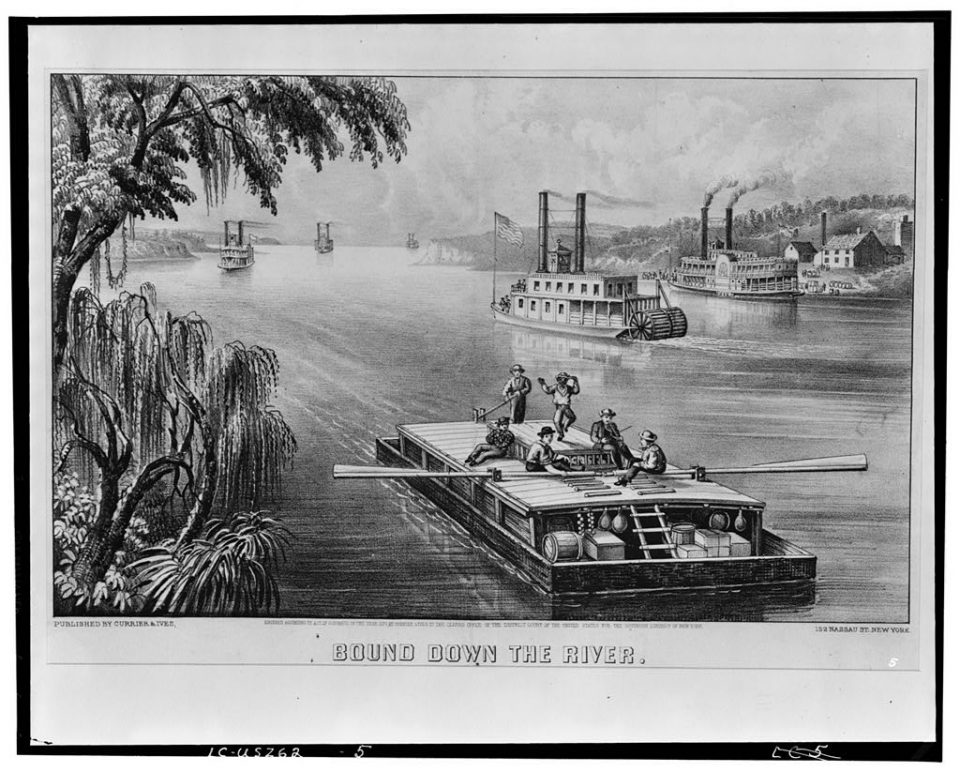

Rivers were popular travel routes too, but they were not much safer. Writing on the The Digital Research Library of Illinois History Journal, Dr. Neil Gale said, “The Ohio River in the 1790s was a teeming inland highway of commerce and emigrants.”

Before the invention of steamboats, travelers went down river on slow-moving flatboats. For river pirates, they were easy targets.

History of Outlaws at Cave-In-Rock

Gale wrote that robbers in the Cave-In-Rock would lure weary boat travelers with warm food, libations, and a place to rest. While they enjoyed their host’s hospitality, members of the gang would secretly search the boat for valuables. Then, after after allowing travelers to float away the next morning, robbers would lie-in-wait further down stream.

Flatboats were slow and heavy. Pirates could easily catch and outrun them in smaller skiffs, canoes, or other smaller, more nimble watercraft.

The Mason Gang

The Mason Gang, headed by Samuel Mason (aka Meason), was a notorious gang of river bandits who operated from (and generally controlled access to) the natural rock formation known since very early days as Cave-In-Rock.

Under the control of the Mason gang, the cave was a hide-out for thieves, murderers, and counterfeiters. As Otto A. Rothert said in his 1923 history of the cave, “It was an ideal lair for river outlaws; it furnished shelter and gave them every advantage over passing travelers.”

Rothert quoted an early traveler — Christian Schultz — who said this after seeing the cave in 1807, “It is a very curious cavern. . . I could not help observing what a very convenient situation this would be for a hermit, or for a convent of monks . . . I have no doubt that it has been the dwelling of some person or persons, as the marks of smoke and likewise some wooden hooks affixed to the walls sufficiently prove. Formerly, perhaps, it was inhabited by Indians; but since, with more probability, by a gang of that banditti, headed by Mason and others, who, a few years ago, infested this part of the country and committed a great number of robberies and murders . . .”

If Gale suggested that travelers were seduced by hospitality, Rothert, in fact, said that ringleader Samuel Mason had actually converted the cave into an inn. He wrote, “Samuel Mason, who had been an officer in the Continental army, converted the cavern into an inn as early as 1797. While he occupied the Cave, and a few years thereafter, it was known as ‘Cave-Inn-Rock.’ It was ideally located. Every passing boat must reveal itself to those in the Cave who had a long, clear view up and down the river. A lookout could detect boats long before boatmen could perceive the Cave.”

The Harpe Brothers: America’s First Serial Killers

For a short time, the Mason Gang shared the cave with two brutal and infamous characters known as the Harpe Brothers. Micahjah and Wiley Harpe were among the most brutal killers to plague the early American frontier. While they were robbers, highwaymen, and kidnappers, they seemed to relish the act of brutal and gory murders most of all. They were prolific and merciless killers, and are widely believed to be America’s first documented serial killers (Wikipedia). Upon capture, Micahjah confessed to 20 murders, but it’s believed the pair killed between 30 and 50 people.

Known has Big Harpe and Little Harpe, there are many variations in their life stories based on unverified information. For example, they probably were cousins rather than brothers. They may have been born in Scotland, but they were probably born in North Carolina. Their names may have actually been Harper, or something else, but it’s debated from source to source. They struck out committing a streak of violent crimes across Tennessee, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Illinois.

Running from the law in Kentucky, the Harpes sought shelter across the river in Illinois at Cave-in-Rock. The Mason Gang welcomed them in, but the Harpes developed a nasty habit of pushing victims naked off the ledge above the cave — something even Samuel Mason couldn’t tolerate, and he ordered them away.

Their other misdeeds are well documented on the Internet, so I won’t dwell on the details here, but both men met violent ends, and both had their heads posted on pikes as a warning to other outlaws.

The Outlaws of Cave-In-Rock: Historical Accounts of the Famous Highwaymen and River Pirates Who Operated in Pioneer Days Upon the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers and Over the Old Natchez Trace by Otto A. Rothert, contains a vivid and excellent account of the lives and crimes of the Harpes. You can read the entire book free on Project Gutenberg.

Shelter for Spirits and Travelers

The cave was occasionally used for other purposes besides an outlaw lair.

Home of the Great Spirit

Some early writers claimed that Native Americans believed the cave to be the home of the Great Spirit or Gitchie Manitou.

Rothert quoted writer Edmund Flagg as saying, “Like all other curiosities of Nature, this cavern was, by the Indian tribes, deemed the residence of a Manito, or spirit, evil or propitious, concerning whom many a wild legend yet lives among their simple-hearted posterity. They never pass the dwelling place of the divinity without discharging their guns (an ordinary mark of respect) or making some other offering propitiatory of his favor.”

Rothert said that official records showed that the territory around Cave-in-Rock was sold in 1803 to the United States by the Kaskaskia tribe. He said the sale was confirmed in 1818 by other tribes of the Illinois confederacy, making it “unchallenged government property. Thus, when the Masons, the Harpes, and other early outlaws held forth there, it was still in the Indians’ territory.”

Shelter for immigrants and settlers

And the cave also served as temporary shelter for settlers heading west.

Rothert recounts one story of a large vessel that anchored at the cave one evening in 1805 after seeing the light of fires inside the mouth of the cave: “As the Nonpareil approached near the mouth of this dreaded cave, a little after twilight, they were startled at seeing the bright blaze of a fire at its entrance. Knowing of its former fame as the den of a band of robbers, they could not entirely suppress the suspicion it awoke in their minds of its being again occupied for the same purpose. Nevertheless, as they had previously determined not to pass this noted spot without making it a visit, they anchored the schooner a little distance from the shore and landed in the skiff. Being well armed with pistols they marched boldly up to the cavern where, instead of being greeted with the rough language and scowling visages of a band of robbers, they found the cave occupied by smiling females and sportive children.

A part of the women were busily occupied with their spinning wheels, while others prepared the evening meal. Their suspicions were not, however, fully removed by all these appearances of domestic peace, still thinking that the men must be secreted in some hidden corner of the cave ready to fall on them unawares. On a little further conversation they found the present occupants of the dreaded cave consisted of four young emigrant families from Kentucky going to settle in Illinois. The females were yet in the bloom of life. Their husbands had bought or taken up lands a few miles back from the river, and after moving their families and household goods to this spot had returned to their former residences to bring out their cattle, in the meantime leaving their wives and children in the occupancy of the cave till their return.”

Thanks for reading.

Be sure to visit me on Facebook, Instagram or Pinterest, or on my website at keithdotson.com.

~ Keith

Sources

The Outlaws of Cave-In-Rock: Historical Accounts of the Famous Highwaymen and River Pirates Who Operated in Pioneer Days Upon the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers and Over the Old Natchez Trace, Otto A. Rothert, 1923

The Digital Research Library of Illinois History Journal, “Illinois ‘River Pirates’ in the Northwest Territory in the 1790s” Dr. Neil Gale

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, “Bound Down the River,” Currier & Ives, 1870

The New York Public Library, Rare Book Division, Digital Collections, “Cave-in-rock, view on the Ohio,” Karl Bodmer, 1840 – 1843