Albumen prints: a resource for students, photographers, and photo collectors

In this blog post, I’ll talk about the history of albumen prints, then I’ll describe the appearance of albumen prints, then I’ll talk about the longevity of albumen prints, and finally I’ll publish a step-by-step process for making albumen paper, as described in 1860.

My hope is this will be useful information for photographers interested in historic processes, and for photo collectors who want to know more before they invest in antique prints.

Photography has always been a science as well as an art. The practice of photography has been a constant march of changing technologies since the very earliest photograph made with light-hardened asphalt on a metal plate down to today, with our increasingly powerful digital sensors.

Quick reference: characteristics of albumen prints

- Thin paper, often mounted on rigid backing board (especially in carte de visite and cabinet cards)

- Coated emulsion, slightly glossy

- Coloration tends to be warm in highlights and deep brown to reddish-brown in image areas

- Dates from 1850s to 1890s

History of albumen prints

The albumen print was first introduced sometime around 1847-1850, in the midst of the daguerreotype era. And while daguerreotype prints were arguably among the most beautiful ever made, they had some problems, namely they were difficult and laborious to make, they were small, and primarily — they created a unique original — meaning you only got one print out of the process.

The albumen print, invented by French inventor and photographer Louis Désiré Blanquart-Evrard, was the first process that was viable for widespread use that allowed for a negative that could produce multiple prints. Albumen prints were popular from the 1850s until the early 20th century.

The term “albumen” comes from the albumen separated from egg whites that was used as a coating for the paper stock, giving the paper a gloss coat that served as an emulsion to support and bind the light sensitive chemicals.

To make the albumen coating, egg yolks were separated from the egg whites, then beaten to a froth, left to settle into a clear yellow liquid, and then mixed with table salt. The paper was coated by floating it on top of the albumen solution in a tray. Then the paper was floated again in a tray of the light sensitive chemicals, and allowed to dry. The glossy albumen coating kept the silver salts above the paper fibers and produced crisp and sharp images compared to other non-emulsion processes like platinum printing.

Albumen prints were a type of contact print, placed directly under the negative and exposed to UV light from the sun. They were not chemically “developed” in the traditional sense we think of now. Instead, they were “printed out” or developed simply while being exposed to UV light. The image appeared on the paper during exposure. Once the print was close to full exposure, it was removed from the light and placed into a fixing bath of sodium thiosulfate which fixed the print’s exposure and prevented further darkening. Often a toner step was included to enhance the color and tones of the print and to aid in longevity.

I’m talking in past tense, but there is still a small group of photographers who make albumen prints today. Modern photographers can use any kind of negative to make the prints, but photographers in the 1850s had to use glass plate negatives since invention of modern film negatives was still decades away.

Albumen prints were made possible by the invention of the wet plate collodion process for creating the negatives. Albumen was also originally used to create the glass plate negs, but the collodion process, invented in 1851, made several improvements — including shorter exposure times.

Wet plate collodion was a process where the glass plate was thoroughly cleaned and then sensitized with the collodion and silver nitrate in a dark room (which was often a dark tent in those days) and then placed while wet into a light-fast plate holder, where it was taken to the camera, exposed, and promptly returned to the darkroom for processing. Because this all takes place within a few minutes, it meant that the entire setup of darkroom, glass plates, and chemicals had to be carried to the location of the photograph.

In my blog post about Carlton Watkins, I talked about how he had to travel to the wilderness of Yosemite in the 1850s with a wagonload of equipment and fragile glass plates to make his lustrous landscape images. And I’ve heard stories of how Edward S. Curtis lost his wagon over the side of a hill with glass plates shattered in the tumble.

However, once you had a successful negative, you could make endless reproductions. According to the George Eastman House, albumen printing technology allowed for the rise of the industrial-scale photography businesses. Travel photographs of places like the Taj Mahal or the Egyptian pyramids became popular items. Photography shops kept flocks of chickens to help them meet the great demand for eggs needed to make the photo papers.

Eventually, industrial grade production companies began making pre-coated albumen papers. As albumen printing took off, plants in Europe and the US made prepared albumen papers for sale to photographers who still had to add the light sensitive emulsions themselves, but at least they didn’t have to fiddle with the eggy part of the process.

Here’s a quote from an article from Eastman House published in 1955 called “60,000 eggs a day,” about the industrial scale of albumen prints in the late 19th century,

“Almost any photograph of the 19th century is printed on very thin, glossy paper and has a deep rich, brown tone. Because this photographic paper was coated with egg white, it was known as ‘albumen paper.’ So great was the demand for this popular product that the Dresden Albumenizing Company, the largest in the world, used 60,000 eggs each day. Girls did nothing all day long but break eggs and separate the whites from the yolks. The whites were then churned and the yolks sold to leather dressers for finishing kid and fine leathers.”

The article includes an illustration of women in long dresses with bustles, working busily in a well lit factory space, surrounded by stacked crates of eggs.

Dresden Germany was the home of the world’s largest suppliers of albumen paper, and they believed that the bacteria growth that came from allowing the egg whites to sit for a few days gave papers an extra high quality of gloss coating, a fact that was contested by other manufacturers — but nonetheless it’s said that a photographer could identify the Dresden paper simply by smell.

What do albumen prints look like?

In that same Eastman House article they describe the look of albumen prints and include the words of its inventor, Blanquart-Evrard:

“The chief physical characteristic of the albumen print is its smooth, glossy surface, which was in contrast to the paper texture of prints made by Fox Talbot’s technique (‘salted paper’) which required no coating.” Blanquart- Evrard was aware of the esthetic qualities of his invention. “Prints on albumen paper,” he wrote, “have a greater warmth of tone, more transparence and precision of detail; but on the other hand, salted paper gives prints which have the aspect of drawings or aquatint engravings, a mysterious vagueness which is pleasing in works of art, because they appeal to the soul as well as to the senses, to the spirit as well as to the eyes. Compositions from nature, portraits, landscapes with large perspective effects, will be more beautiful on salted paper; but albumen papers have the advantage when it is a question of reproducing natural history specimens and buildings, where detail, precision and delicacy are the most important qualities.”

It’s funny — the sharp glossiness of albumen prints actually became controversial in the 19th century, with some people calling their vividness “vulgar.”

Most albumen prints have a yellowish coloration resembling sepia prints, with warm background and reddish or deep brown darks. In a video available on YouTube, a George Eastman House curator shows us two albumen prints side-by-side — one that has not degraded looks neutral, with white paper and black and white tones similar to the deep eggplant color of a selenium print. The other displays the characteristic warm and brown look of most albumen prints, a state she refers to as “albumen deterioration.”

The silver image particles produced in silver printing-out papers are much smaller than the image particles produced by silver prints processed in chemical developers. Remember, printing-out papers are ones where the image develops in the sun. The smaller silver particles create a phenomenon known as light scattering, which means that images made on printing-out papers do not appear neutral black, but instead appear brown, red, or yellow. With albumen prints a gold or selenium toning step was included to produce a purple or purplish-brown look. And I got that information from a very thorough article called “The History, Technique and Structure of Albumen Prints,” published in 1980 by James M. Reilly. We’ll hear more from him in a minute.

Whereas a large daguerreotype would have been about 6 inches x 9 inches, albumen prints could be as large as any negative would allow. Pre-coated albumen papers came in sheets that were 23 x 18-inches in a ream of 480 sheets that cost $10 in 1860. Eadweard Muybridge, who is better known for his motion study images, made a stunning untitled albumen print of the Pigeon Point Lighthouse on the California coast in 1868 that is 21.25 x 16.5-inches in size.

The photograph was one of many Muybridge photographed along the west coast from San Diego to Washington State for the Lighthouse Board. The photograph features the lighthouse dramatically perched atop a rocky promontory overlooking the Pacific Ocean, with a curve of rocky coastline sweeping across the foreground. You can see the image on the museum’s page. This print portrays the deep reddish browns characteristic of an albumen print.

Another Muybridge image is the absolutely luminescent “Valley of the Yosemite, from Rocky Ford”, 1872 which was printed at 16.88 x 21.45-inches

Below is an old albumen print cabinet card that I own as part of my own small photo collection. It was made by Minnesota-based photographer Carl Thiel between 1887 and 1891, dates established by his occupancy dates at the Ingalls Block studio space.

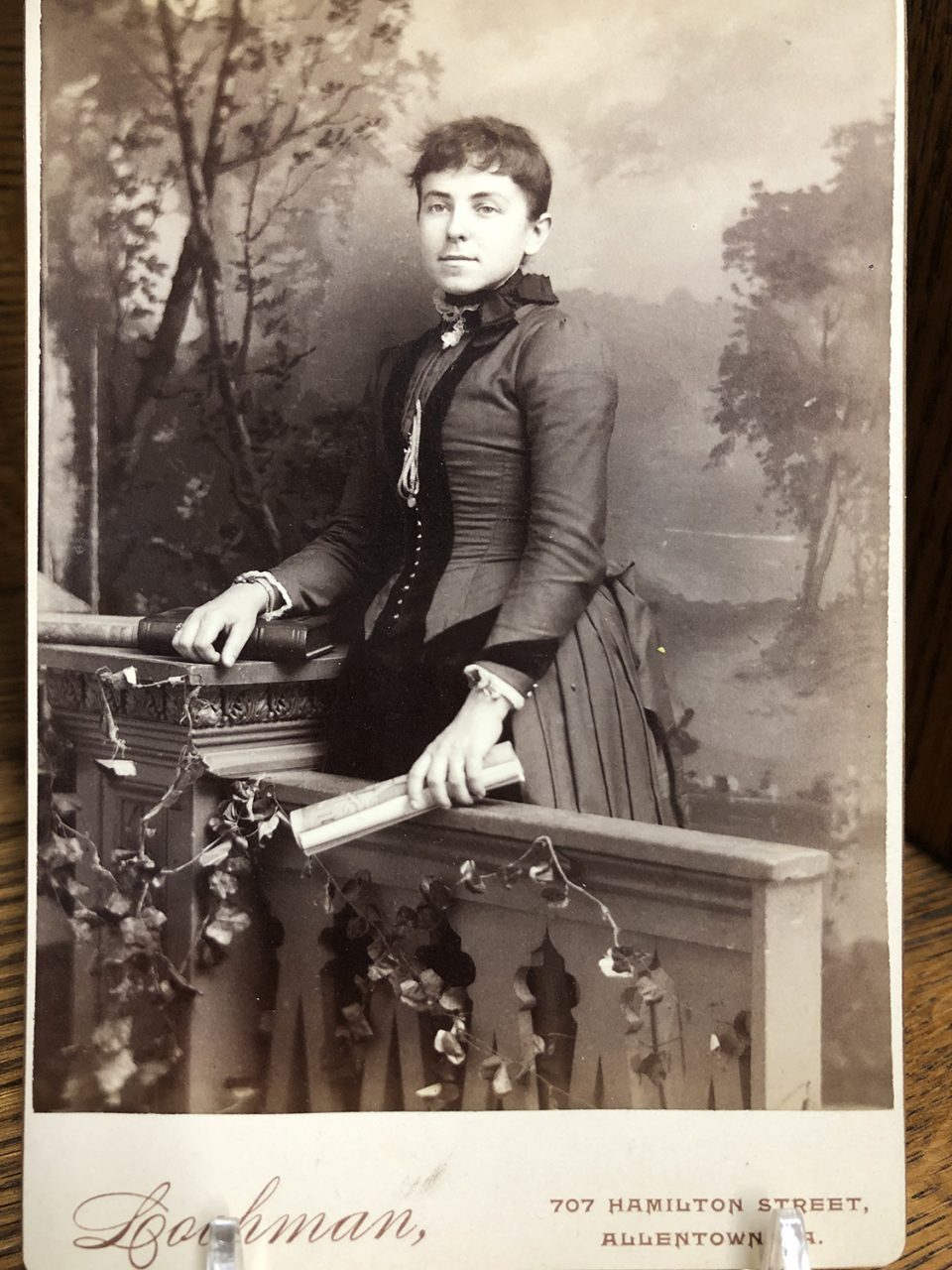

Above, another photograph from my personal collection. Easy-to-produce albumen prints helped create a craze for cabinet card portraits like this one.

How stable are albumen prints?

Now let’s talk briefly about concerns of conservation and preservation in albumen prints. Even within a decade or two of its invention, the permanence of albumen printing was called into question. Imperfections in the fixing chemistry or process meant prints would fade and yellow rapidly. Even prints kept carefully stored for decades to prevent fading may be susceptible to damage if improperly displayed today.

Again from Reilly’s “The History, Technique and Structure of Albumen Prints,” we learn about some of the concerns with the longevity of albumen prints:

“Unfortunately, albumen prints as a group merit the urgent concern and attention of conservators. Very few survive in original condition. Approximately 85% of extant albumen prints suffer from the presence of a yellowish-brown stain in the highlights (non-image areas), and almost as many exhibit overall image fading, with an accompanying shift in image color from purple or purplish-brown to a sickly yellowish-brown. Deterioration often includes a partial or severe loss of highlight detail. The staining, fading and color change may range from slight to very severe, but the extent of deterioration In albumen prints as a whole Is much more advanced than in nearly every other variety of photographic paper, including types which pre-date albumen papers.”

When paper manufacturers began selling more modern gelatin silver photo papers in the 1890s, they were sure to mention the instability of albumen papers in their ads.

The albumen paper coating process step-by-step, as described in 1860

Following is a step-by-step process for making albumen paper, as published in The Photographic News on June 29,1860, p.101,

“On the Preparation of Positive Paper” by M. Aleo

- Preparation of the Albumen — Break the eggs into a graduated measure, carefully avoiding the mixture of yolk with the whites, and when the desired quantity of albumen is obtained separate the germs and pour the whites into a glazed earthen vessel, and to every 100 parts add 5 parts of a soluble chloride (that of ammonium is best), first dissolving it in as little water as possible. The quantity of water must not exceed one-tenth of the albumen, if a very brilliant surface on the proofs is desired. Beat the whites into a froth, and, after allowing it to settle for five minutes, remove the froth with a fork into a hair sieve, or muslin strainer placed over a second vessel. This operation to be continued whole of the whites are beaten into a froth and strained.

Allow the filtered albumen to settle for twelve hours; it is then ready for use. Draw sufficient quantity off into a shallow glass or Porcelain dish, without disturbing the sediment. It is a good precaution to strain it through a piece sponge placed in the neck of a glass or porcelain funnel. When circumstances permit, it is best to allow the albumen to repose four or five days before use. It appears to clarify itself, and gives a more brilliant surface to the positive paper. - Preparation of the Paper — The positive paper must be carefully selected, and experimented upon. before the preparation of a large quantity is undertaken. If it be unequally sized, it will give uneven proofs and unsatisfactory results. Even the cutting of the paper to the required size demands much care, and only one sheet should be cut at a time, with an ivory paper-knife, without pressure or creasing.

Mark the back of the paper, and place it, sheet by sheet, carefully on the albumen without allowing the liquid to flow on to the back of the paper. This operation is best performed in damp weather, for then the albumen takes to the paper more readily, without forming bubbles, and the paper also dries more slowly and evenly. The first sheet floated is almost always defective.

Some little dexterity is required in floating the paper on the albumen; the description of which is difficult, and necessarily unsatisfactory. The time which the paper should be allowed to float upon the albumen will vary with the thickness and sizing of the paper: two minutes and a half may be taken as the average. It must not be reversed until it lies flat on the surface of the liquid. When this ensues, take the sheet by the two most distant corners, which, before it was floated on the albumen, have been previously folded back, and raise it slowly and regularly, so that the albumen forms a continuous, even coating over the whole surface. If the paper be raised too quickly, the albumen will flow down the paper in streaks, and the surface will dry uneven. By taking the paper at the corners most distant from each other, and suspending it to drain and dry in that position, the risk of drying unevenly is avoided. - Hanging and Drying the Paper — The manner of hanging and drying the paper is one of the most important points, to avoid unevenness. The following method has always been successful, without causing any embarrassment to the operator:

Take two pieces of stout whipcord, and wax them, to prevent any fragments falling on to the wet paper; and string on each pieces of thin cork, of about an inch or an inch-and-half square, with holes pierced in the centre, through which the cord can freely pass. The cords are fastened to two walls, parallel to each other, with three bars of wood placed at equal distances along the cords to keep them apart; the distance must be a little greater than the width of the albumenised paper. Through each piece of cork a black-varnished pin must be passed upwards in a slanting direction, which penetrates the corners of the paper without difficulty. Care must be taken that the paper hangs fully distended and even, for, if it becomes curved, the albumen will dry upon its surface unequally. and spoil the proofs taken upon it. According to the extent of the operations, so may these suspending appliances be inch plied; they have the advantage of taking up but little room, and are easily removed when the operation is over. The albumen that drains from the paper can be collected in dishes or on sheets of waste paper spread on the floor.

Thanks for reading.

Be sure to visit me on Facebook, Instagram or Pinterest, or on my website at keithdotson.com.

~ Keith

Sources and Links

George Eastman House, “The Albumen Print: Photographic Processes,” YouTube

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cq1RvahEPSk&ab_channel=GeorgeEastmanMuseum

George Eastman House, “60,000 Eggs a Day,” Beaumont Newhall, 1955

https://web.archive.org/web/20160304084043/http://image.eastmanhouse.org/files/GEH_1955_04_04.pdf

The Oakland Museum of California

https://museumca.org/exhibit/inspiration-points-masterpieces-california-landscape

The Oakland Museum of California, Eadweard Muybridge, untitled photograph of the Pigeon Point Lighthouse

http://collections.museumca.org/?q=collection-item/a72224

Or get a better look here

https://www.flickr.com/photos/14096169@N07/1517810098/

Link to my own personal sample of an albumen print by P. Sebah and Lekagian

https://icatchshadows.com/antique-albumen-print-eqypt/

The Photographic News, “On the Preparation of Positive Paper,” June 29, 1860, p.101, M. Aleo

https://cool.culturalheritage.org/albumen/library/c19/aleo.html

Rochester Institute of Technology, “The History, Technique and Structure of Albumen Prints,” James M. Reilly, 1980

https://cool.culturalheritage.org/albumen/library/c20/reilly1980.html

Wikipedia, “Albumen print”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albumen_print

Wikipedia Commons, Eadweard J. Muybridge, “Valley of the Yosemite, from Rocky Ford,” 1872

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Eadweard_J._Muybridge_(American,_born_England_-_Valley_of_the_Yosemite,_from_Rocky_Ford_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg